GameRoy: JIT compilation in High-Accuracy Game Boy Emulation

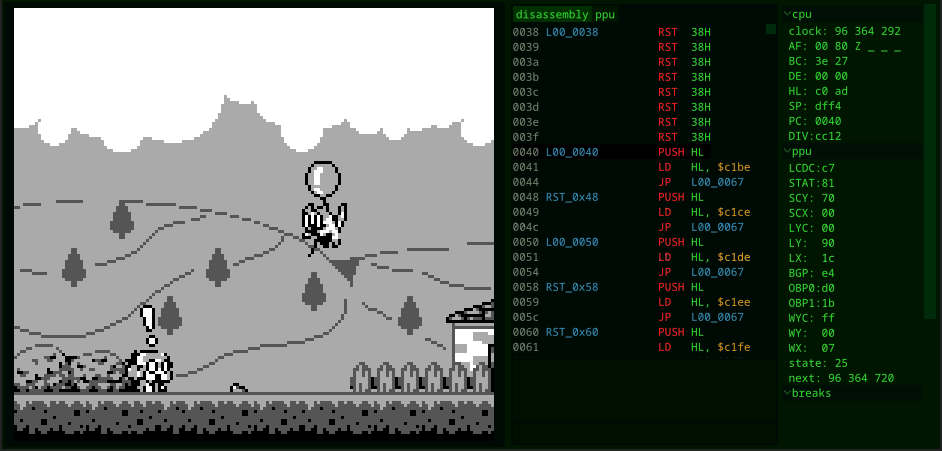

Over the past two years, I have spent a lot of time working on my Game Boy emulator, GameRoy. It has reached a good point, where it has a GUI interface (including a debugger and disassembler) and passes numerous tests (comparable to some of the most accurate emulators). I even made a port to Android!

However, there’s always been something that I wanted to do, even before developing this emulator: implementing a dynamic recompiler, also known as a JIT compiler. Since the first time I researched how an emulator works, one of the initial descriptions I found was about the distinction between interpreters and dynamic recompilers. This made me very interested in the subject.

Reinspired by JIT compilers (such as those in Java, JavaScript and LuaJIT), by Dolphin’s development posts, and primarily by this blog post by Brook Heisler regarding a JIT compiler for NES, I began implementing one in my emulator.

One intriguing point in Brook Heisler’s post was a limitation in how interrupts were handled in the compiled code. When developing his JIT compiler, he encountered a trade-off between performance and precision in how to handle interrupts in his emulator. He ultimately decided to sacrifice performance for precision, but I was not satisfied with that approach.

After pondering for some time, I came up with a solution to this problem - a way to achieve maximum performance without sacrificing precision.

In this blog post, I will describe the process and considerations of implementing a JIT compiler in my emulator, and how I solved the problem of handling interrupts.

It’s worth noting that I am presenting the topics in the same order they came up in my thought process, which just happens to be the reverse order in which they were implemented (excluding the interpreter).

Interpreter x Just-In-Time compilation §

An emulator has the job of reproducing a computer system’s behavior in software. A computer system, including the Game Boy, consists of many components, each requiring emulation. Among these, the CPU stands out as the most crucial component, responsible for directly executing the instructions of the programs that you intend to run on your emulator.

There are two main ways of emulating the CPU (or any programmable component).

A very basic interpreter §

The simplest way to emulate a system’s CPU is by implementing an interpreter. Essentially, the interpreter reads instructions from the emulated memory, decodes them, and emulates their execution by updating the emulator’s state.

For the Game Boy, the instruction to be executed is read byte by byte (since the Game Boy is an 8-bit system) from the memory address pointed by the program counter (PC), incrementing the PC after each read. To decode the instruction only the first byte is needed for most instructions. Since there are only 255 possible values for a byte, we can use a look-up table. The Game Boy CPU also has 0xCB prefixed instructions that are decoded from the second byte, using another look-up table.

I am using Rust for my emulator implementation, so I can use a match statement

to decode the instruction. Each branch of the match lead to a function that

implements the instruction’s execution. This function reads and writes to

registers or memory, reading additional bytes from the instructions when

necessary (e.g., for immediate values, like the address of jump instructions).

A very simplified interpreter would be something like this:

fn interpret_instruction(gb: &mut GameBoy) {

let opcode = gb.read(gb.cpu.pc);

gb.cpu.pc += 1;

match opcode {

0x00 => nop(gb),

0x01 => load_bc_im16(gb),

0x02 => load_bc_a(gb),

0x03 => inc_bc(gb),

0x04 => inc_b(gb),

// 252 more branches like that...

}

}

// ...

// INC B 1:4 Z 0 H -

fn inc_b(gb: &mut GameBoy) {

gb.cpu.b += 1; // increment B

gb.cpu.f &= 0x1F; // clear Z, N, H flags

if gb.cpu.b == 0 { gb.cpu.f |= 0x80; } // set Z flag on zero

if gb.cpu.b & 0xF == 0 { gb.cpu.f |= 0x80; } // set H flag on half carry

}

The interpret_instruction function is invoked in a loop, executing one

instruction per iteration.

One issue with this approach is that the speed at which the interpreter can execute the code is far behind the theoretical speed that your computer’s CPU could execute the code.

The interpreter requires multiple instructions of the host CPU, not only to execute the instruction, but also to read from memory and decode it, task that the host CPU does in a single instruction. Not only that, the interpreter needs to decode the same instruction multiple times.

But that isn’t a problem, at least not for the Game Boy, whose CPU runs at a clock speed of just a little over 1 MHz, while you might be reading this on a device with much more than 1 GHz. In fact, GameRoy can run Game Boy games at over 60 times the original system’s speed on my notebook with a 2.6 GHz Intel i5-4200U.

Even so, this is still 41 times slower than the theoretical speed that my CPU can execute the code! (If you assume the same number of instructions per instruction not very reasonable, actually). Yet, there is a very interesting technique that can be used to close this gap: recompilation.

A very basic JIT compiler §

The second way of emulating the CPU is by translating the instructions of the Game Boy CPU into the instructions of the host CPU and then executing them. This method is called recompilation. In the case of the Game Boy, as well as in many other systems, you can not recompile all the code contained in a program beforehand (known as static recompilation). Therefore, you need to perform that translation at runtime, which makes the technique be called dynamic recompilation, or more commonly called, Just-In-Time compilation (or JIT).

To achieve this, you need to create a compiler. The compilation process is very similar to the interpreter, where you read, decode and execute instructions. But instead of executing the instruction directly, it will generate the corresponding machine code that will.

The machine code can be generated just once and then executed multiple times, bypassing the overhead of reading and decoding instructions of the interpreter.

In a simplified form, the code for the compiler would look something like this:

fn compile_instruction(ctx: &mut JitCompiler, gb: &GameBoy, code: &mut Vec<u8>) {

let opcode = gb.read(ctx.curr_pc);

match opcode {

0x00 => nop(ctx, gb),

0x01 => load_bc_im16(ctx, gb),

0x02 => load_bc_a(ctx, gb),

0x03 => inc_bc(ctx, gb),

0x04 => inc_b(ctx, gb),

// 252 more arms like that...

}

}

// ...

// INC B 1:4 Z 0 H -

fn inc_b(_: &mut JitCompiler, code: &mut Vec<u8>) {

code.extend(&[

0x0f, 0xb6, 0x47, 0x01, // movzx eax,BYTE PTR [rdi+0x1] ; read F

0x0f, 0xb6, 0x4f, 0x02, // movzx ecx,BYTE PTR [rdi+0x2] ; read B

0xfe, 0xc1, // inc cl ; increase B

0x88, 0x4f, 0x02, // mov BYTE PTR [rdi+0x2],cl ; write B

0x24, 0x1f, // and al,0x1f ; clear Z, N, H flags

0x8d, 0x50, 0x80, // lea edx,[rax-0x80] ; calculate the flags...

0x0f, 0xb6, 0xc0, // movzx eax,al ; ...

0x0f, 0xb6, 0xd2, // movzx edx,dl

0x0f, 0x45, 0xd0, // cmovne edx,eax

0x8d, 0x42, 0x20, // lea eax,[rdx+0x20]

0xf6, 0xc1, 0x0f, // test cl,0xf

0x0f, 0xb6, 0xc0, // movzx eax,al

0x0f, 0x45, 0xc2, // cmovne eax,edx

0x88, 0x47, 0x01, // mov BYTE PTR [rdi+0x1],al ; write F

]);

}

This compile_instruction function reads and decodes an instruction, and then

writes the machine code that executes that instruction to a buffer.

(For the curious, I got that assembly/machine code by simply implementing the

instruction in Rust, and then disassembling it with objdump

-d.)

So, to create a JIT compiler, you only need to run compile_instruction on the

sequence of instructions starting at the address the PC is currently, write

the code to a memory page with executable permission (you can use a crate like

memmap2 for that), transmute it into a

function pointer, and call it! Simple as that!

Well, actually, some instructions that involve function calls in their implementation or include branching are much trickier to implement than just appending a static array of bytes to a buffer. You also need to make sure that the code for each instruction can work together, using the same registers and so on. You also need a prologue and epilogue for the function that satisfies a calling convention.

However, this already shows the basics of a JIT compiler.

Also, in my actual implementation I used the crate dynasm for

emitting the machine code (this crate has a macro that translates assembly code

into machine code at compile time), so the code is much more maintainable than

the array of raw bytes that I presented here.

Optimizations §

The cool thing about compiling code is that you can do optimizations! For example, one of the (few) optimizations that I made in the JIT compiler for my emulator is the omission of unnecessary flag calculations (directly inspired by the one described in Brook Heisler’s post).

If you tried to read what the assembly code is doing, you may have noticed that only four instructions are used to increment the value of register B, and the remaining 10 are being used to update the conditional flags in the register F. But the value of F may be overwritten by the next instructions before it could be read from a conditional jump instruction for example. In that scenario, updating the value of F does not affect the behavior of the emulation, so it is a waste to compute.

If we compile all these instructions together, we can detect that kind of scenario and omit the flag calculation, greatly reducing the amount of code emitted!

// INC B 1:4 Z 0 H -

fn inc_b(ctx: &mut JitCompiler, code: &mut Vec<u8>) {

if !ctx.flag_is_need {

code.extend(&[0xfe, 0x47, 0x02]); // inc BYTE PTR [rdi+0x2]

return;

}

code.extend(&[

0x0f, 0xb6, 0x47, 0x01, // movzx eax,BYTE PTR [rdi+0x1] ; read F

0x0f, 0xb6, 0x4f, 0x02, // movzx ecx,BYTE PTR [rdi+0x2] ; read B

0xfe, 0xc1, // inc cl ; increase B

0x88, 0x4f, 0x02, // mov BYTE PTR [rdi+0x2],cl ; write B

0x24, 0x1f, // and al,0x1f ; clear Z, N, H flags

0x8d, 0x50, 0x80, // lea edx,[rax-0x80] ; calculate the flags...

0x0f, 0xb6, 0xc0, // movzx eax,al ; ...

0x0f, 0xb6, 0xd2, // movzx edx,dl

0x0f, 0x45, 0xd0, // cmovne edx,eax

0x8d, 0x42, 0x20, // lea eax,[rdx+0x20]

0xf6, 0xc1, 0x0f, // test cl,0xf

0x0f, 0xb6, 0xc0, // movzx eax,al

0x0f, 0x45, 0xc2, // cmovne eax,edx

0x88, 0x47, 0x01, // mov BYTE PTR [rdi+0x1],al ; write F

]);

}

Fantastic! The optimized version is 14 times smaller than the unoptimized one!

There are, of course, many other optimizations that can be done. These could reach the point where the optimizations become by far the most complex part of a compiler. Instead of implementing them your-self, you could use a third party compiler infrastructure, like LLVM or Cranelift, which implement many optimizations for you.

But my emulator is, at least for now, only targeting x86-64 machine code. So

I will refrain from using any of them.

But there is a big problem in trying to apply any non-trivial optimization, even the simple flag omission one: the fact that the CPU needs to handle interrupts.

Interrupts §

Interrupts are a mechanism that allows the CPU to stop the execution of the current code and start executing a function that handles the interrupt. For example, in the Game Boy, you can use the interrupt triggered by the VBlank of the PPU (which occurs right after the screen is fully rendered) to update the game logic and prepare the next frame for rendering.

There are multiple sources of interrupts in the Game Boy, which are triggered by one of the various components. So to handle the interrupts we also need to update them.

And if you want a precise enough emulator, you need to update the components and

check for interrupts before every single instruction. Not only that, if you

pursue cycle-accuracy, you also need to update the components before each memory

access. One way of doing that is by using a tick function.

Our interpreter becomes something like this:

fn interpret_instruction(gb: &mut GameBoy) {

if gb.interrupts_enabled & gb.interrupts_flags != 0 {

// this will write to the stack, and change PC to the interrupts handler

handle_interrupt(gb);

}

let opcode = gb.read(gb.cpu.pc);

gb.cpu.pc += 1;

tick(gb, 4); // each memory access takes 4 cycles

match opcode {

// ...

0x36 => ld_hl_im8(gb),

}

}

fn tick(gb: &mut GameBoy, cycles: u64) {

gb.clock_count += cycles;

gb.update_timer(clock_count);

gb.update_ppu(clock_count);

gb.update_sound_controller(clock_count);

gb.update_serial(clock_count);

}

// LD (HL),d8 2:12 - - - -

fn ld_hl_im8(gb: &mut GameBoy) {

let value = gb.read(gb.cpu.pc);

gb.cpu.pc += 1;

tick(gb, 4);

let address = gb.cpu.h as u16 * 0x100 + gb.cpu.l as u16;

gb.write(address, value);

tick(gb, 4);

}

Ignoring all the complexity of emulating each component and some quirks with interrupt handling timing, this is roughly how the interpreter handles the interrupts.

However, handling interrupts poses a problem for our JIT compiler. Not only might constantly checking for interrupts introduce a considerable amount of overhead, but we can no longer apply many of the optimizations that we would like to do, like omitting calculation, because the code needs to always be prepared to branch to the interrupt handler.

You could try to check for interrupts only every 10 instructions or something; it may be precise enough for most games (but not all). But my emulator pursues maximum accuracy, and the point of the JIT compiler is to determine if it’s possible to implement it, without sacrificing precision or performance.

And I have figured out a way to achieve that: by estimating when the next interrupt will happen.

Estimating the next interrupt §

The JIT compiler in GameRoy works this way: given the current address in the PC register and the bank currently mapped to that address, the compiler produces a block of instructions starting at that address. This block is then compiled down into machine code, and stored in a cache.

Before executing the block, it checks if an interrupt will happen during its execution. If not, the block is executed, otherwise, we fall back to the interpreter.

This allows us to apply all the optimizations that we want, without worrying about interrupts (for the most part).

The disadvantage is that we still need to have an interpreter around, and the fallback may decrease the emulator’s performance. However, I already had an interpreter working, so there’s no problem with that. Only a small fraction of the instructions need to be interpreted, so the loss of performance is not so bad. An alternative is to use, as a fallback, a version of the compiler that handles interrupts.

The main challenge in this approach is estimating when the next interrupt will happen. Depending on how a component generates interrupts, it may just not be possible to estimate when the next interrupt will happen more efficiently than just emulating the component until it occurs.

Thankfully, in the case of the components of the Game Boy, it is possible to estimate the instant of the next interrupt in constant time. But implementing the estimation is still tricky, with a lot of edge cases. Thanks to a lot of fuzzing-based testing, I am somewhat confident that I got it right.

If you want to take a look at how the implementation looks like, here are links for the timer, for the PPU, and for the serial. The fuzz tests are at the bottom of the same file, if you also want to take a look at them.

Lazy Update §

And with that we fix the problem with interrupts! But we still need to update the components. But thankfully we only need to update the components before accessing a memory address that is mapped to a component or right before an interrupt is triggered. So we can just update the components in the memory access function, right before reading or writing to memory, and before checking for interrupts in the interpreter.

To implement that, each component will contain a clock count of the last time it was updated, and a function that updates the component to the current clock count. The cool part is that this allows us to further optimize the emulation of each component. By decreasing the number of times we update each component we save some work, and emulating many cycles at once allows more efficient emulation.

The implementation of the PPU is a good example of that. The PPU is the component responsible for transforming the tile map and sprite data into pixels for the screen. The final rendering result is somewhat straightforward to emulate if the input data doesn’t change. But the necessity of taking into account that the CPU may be changing the input during rendering makes it necessary to emulate the complex inner workings of the PPU.

But when we lazily update the PPU we can be sure that there were no changes since the last update, allowing us to bypass most of the complexity of the PPU, just emulating the final rendering result, which is much faster.

In the figure below we can view the time spent emulating the PPU, when updating it every instruction and when updating only when necessary.

The draw_scan_line function renders the final result of a scan line, without

emulating the entire PPU’s inner workings. Doing the math, it is possible to see

that the emulation of the PPU gains a speed-up of almost 10 times, increasing the

overall speed of the emulator by 4.

One thing to notice is that before this optimization, only 14% of the time was spent in the CPU. That means the CPU emulation was hardly the bottleneck of the emulator, and the JIT compiler would not provide a significant speed-up. But after this optimization, the CPU emulation is responsible for 63% of the time, giving some room for the JIT compiler to shine.

The Compiler a little more in depth §

Above, I’ve just provided a simplified version of how a JIT compiler would work. However, the actual implementation concerns itself with more details.

First, it needs to decide which group of instructions to compile. For that, I have a step for “tracing a block”, which basically starts at a given address (very likely the current address in the PC register) and decodes instructions one after the other, until it reaches an unconditional branch (like a jump or a call). This produces a block for that address.

Currently, the blocks are just linear sequences of instructions, but I could very well also expand the block tracing to follow branches and potentially compile big sections of the program at once. However, my block caching is still too suboptimal for that (I explain it in the “Remaining Work” section).

An important point is that I only trace blocks when the PC is pointing to an

address in the memory ROM (range 0x0000 to 0xFFFF). If it is pointing

outside of it, like the RAM, I just fall back to the interpreter. This allows me

to avoid handling self-modifying code, which is a general problem for dynamic

recompilers. Also, games in general don’t run much code in RAM, so it’s not that

big of a loss.

Another point is that the Game Boy uses bank switching, which means that different memory banks may be mapped into the same addresses at different times. So, a block needs to be identified not only by its starting address but also by a bank number.

After tracing a block, the compiler compiles it down to a function. It emits machine code for the function prologue (align the stack, push registers, etc.), and then emits the machine code for each instruction.

Instructions that update registers work like the one I gave as an example before. They just load the registers from memory, do the operation, and store them back. A much more efficient way would be to keep the Game Boy registers in the x86-64 registers for as long as possible, but I still haven’t implemented that.

Instructions that may branch check if the target address is inside the block,

and if it is, they emit a jump to the target address inside the block. This uses

dynasm helper for emitting jumps. If the target isn’t in the block,

it just emits the prologue for the block (pop registers and call ret).

Instructions that read or write to memory emit function calls to Rust functions that handle the memory access. This allows me to handle cases where it may change the emulator’s state, like the lazy update of components. But memory access with an immediate address may be emitted inline if possible.

Another important point is that writing to memory may trigger an interrupt, or at least change its timing. This means that after each write, the compiler needs to emit another check for interrupts, exiting if necessary. The same is true for bank switching: a write to ROM could switch the bank that the block is currently executing, so it needs to check if it did change and exit the block.

Also, because writes can trigger interrupts and the interrupts can read the content of flags, each write also compromises inter-instruction optimizations, like the omission of flag calculations that I mentioned earlier.

And because there are now multiple checks for interrupts throughout the block, each check only needs to make sure that the next interrupt will not happen before the next interrupt check, including the initial check that happens before entering the block.

After finishing emitting the block, the compiler moves the buffer with the

machine code to an executable memory region and stores it in a HashMap, which

maps (bank, address) to the block. Now, whenever the emulator needs to execute

this block again, it just gets it from the HashMap (or compiles it if it isn’t

there yet).

Results §

The entire point of implementing a JIT compiler is to improve the performance of the emulator. So, how much of a speed-up did I get?

First, let’s compare the speed of the interpreter and the JIT compiler. For that, I ran the emulator with two different games and measured the time it took to run each game for 100 seconds. The first game is The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening, and the second is Tobu Tobu Girl. Both games have a nice start screen animation, which may be a good benchmark for the speed of the emulator.

The emulator was capable of emulating Tobu Tobu Girl more than 100 times faster than the real system! However, when comparing the two implementations, it’s possible to see that the JIT compiler decreases the execution time by about 40% in Tobu Tobu Girl and about 30% in Zelda. This is not the massive speed-up I was expecting, but it is still very significant.

We can also take a closer look at the time spent emulating each component. By

using blondie or inferno to capture a stack trace and

passing it to my plot script, I can generate the following pie charts:

From the pie chart above, we can see that a big chunk of the time is spent emulating the PPU. We can also see that Zelda has a lot less opportunities for optimizing the PPU, and therefore spends more time in it, which explains why it is much slower and has a smaller speed up.

Looking just at the interpreter (blue) and JIT (red) sections, we can roughly

estimate that the JIT compiler is about 4 times faster than the interpreter.

However, a considerable amount of time is still spent just querying the block in

the HashMap. And even with the JIT compiler, some time is still spent in the

interpreter.

Another aspect we can explore is comparing the emulator with others out there. I picked 5 emulators that are relatively popular and have a high degree of accuracy: SameBoy, BGB, Beaten Dying Moon, Emulicious and Gambatte-Speedrun.

You can get a feel for how accurate each emulator is by viewing the test results in daid’s GBEmulatorShootout. Notice that these tests include DMG, GBC, and SGB versions of the Game Boy, but GameRoy only emulates DMG, so it appears a little behind the others.

The emulators were run on Windows, with their default GUI frontend, configured to emulate DMG and with “turbo mode” or “fast forward” or whatever it is called enabled. Due to the use of a GUI frontend, the measurement being based on video recording, and the intro being run only two or three times, the results are not that precise. But hopefully they are good enough to compare them with each other.

To measure the performance of each emulator, I ran the same two games as before, and measured the time it took to run the intro animation of each game, using a video recorded with OBS Studio. For Tobu Tobu Girl, I let the intro run three times, and for Zelda, I let it run twice.

An important point is that both BGB and Gambatte (at least, I’m not sure if the others do something similar) have optimizations that skip the rendering of some frames of the LCD, which is something that I haven’t implemented yet in my emulator. That optimization can be disabled in BGB, so I included it in the benchmarks to have a more direct performance comparison. For Gambatte it is not possible to disable it1.

Here are the results2:

Based on these results (and if you ignore the emulators that do frameskip optimization and the lack of rigor in the benchmark), I can somewhat claim that GameRoy is the fastest emulator!

Interestingly, even the interpreted version of my emulator is faster than most of the other emulators when running Tobu Tobu Girl. This is likely due to the PPU optimization achieved by implementing lazy updates and estimating the next interrupt, as The Legend of Zelda emulation speed is still comparable to the other emulators and it less affected by PPU optimization.

But both Gambatte and BGB with frameskip optimization are a lot faster than GameRoy. BGB is more than 5 times faster than its non-optimized version (which is closer to the 4 times speed-up that I got with PPU optimization in the Interpreter version of GameRoy) and is more than 2 times faster than GameRoy.

If I implement the frameskip optimization, somehow eliminating the entire time spent in the PPU, my emulator would become about 2 times faster than it is now, which still would not be enough to beat BGB. So the claim that GameRoy is the fastest emulator may be a little exaggerated.

Errata: The emulator benchmarks included in the first published version of this blog post were using an older version of GameRoy, didn’t include Gambatte, and were running BGB with its maximum speed capped at 10x. In that scenario, I had claimed that GameRoy was the fastest emulator by far. I hope I have fixed it now.

Remaining work §

I may have achieved the state-of-the-art regarding dynamic recompilation applied to Game Boy emulation (the only related work that I know of is JitBoy), but my implementation is still far from perfect.

The first thing is that I am not implementing some obvious optimizations. For

example, I am not keeping the Game Boy registers loaded in the x64 registers,

but instead, I am loading and saving them to memory every instruction. The only

register that I optimize is the PC register, whose value I can know at compile

time, so I only update it on block exit.

The flags are the most suboptimal, as I am computing the value of the flag, encoding it in the F register bit flag, and then later decoding them in the branch instructions, where I could be using the value of each flag directly between instructions.

But I will probably not implement these optimizations, at least not directly. Instead, I plan to write another backend for the compiler using Cranelift, which will likely automatically handle these optimizations and more. I have already done some experiments with it before, and it seems to work pretty well. It will also help with porting the JIT compiler to run on Android.

Another inefficiency in my JIT compiler is regarding redundant

recompilations. Currently, I am building an entire block for each (bank,

address) entry point, even if that same address is already in the middle of

another block. This means that many of the blocks are overlapping, introducing

unnecessary compilation time and memory usage.

I don’t know if this is a big problem (I need to do some profiling first), but I

could fix it by including in the HashMap a key for the address of each

instruction in the block and moving the block prelude to a Rust naked function,

that jumps to the middle of the block.

However, this would introduce some complications, like filling the HashMap

with too many keys, and the need to ensure that each compiled instruction can be

jumped to. This last point may be a problem for optimizations, but I haven’t

given it too much thought yet.

Conclusion §

And that’s it! I was not able to achieve the massive speed-up I was expecting, but I still managed to make my emulator the fastest one out there, even if the generated code is far from optimum.

I would like to thank Brook Heisler for his blog post, “Experiments In NES JIT Compilation”, which inspired me to try this out, and gave me some useful links on how to implement a JIT compiler, like Eli Bendersky’s Adventures In JIT Compilation series, which I re-implemented in Rust as a learning exercise.

If you want to take a look at GameRoy, I invite you to check out its GitHub repository.

-

Another point is that the frameskip in Gambatte, unlike BGB, is not dynamic. You need to provide a fixed number of frames to skip, and the unskipped frames are still emulated at a maximum of 60 frames per second. I configured the frameskip to 753, which made the GUI lag a littke (hopefully, this means it is running at maximum speed), but be aware that this choice is arbitrary and may not be optimal. ↩

-

You can also see the raw data collected here. ↩

-

The emulator has a hard cap of 16 in the frameskip configuration, but I modified the source code to disable that limit. ↩