Compiling Brainfuck code - Part 3: A Cranelift JIT Compiler

This is the third post of a blog post series where I will reproduce Eli Bendersky’s Adventures In JIT Compilation series, but this time using the Rust programming language.

- Part 1: An Optimized Interpreter

- Part 2: A Singlepass JIT Compiler

- Part 3: A Cranelift JIT Compiler

- Part 4: A Static Compiler

In the previous part we made an x86 JIT compiler for brainfuck interpreter. In this part we will make a JIT compiler using the Cranelift machine code generator.

What is Cranelift §

Cranelift is a machine code generator written in Rust, similar to tools like LLVM or GCC’s backend. As briefly discussed at the end of the last part, these tools are used to create an abstraction layer between language implementations and their compilation targets, by means of a target-independent intermediate representation (IR).

This means that instead of each language having a compiler for each target (a quadratic amount of work), each language compiler can instead target the code generator IR, and the code generator has a backend for each compilation target (a linear amount of work).

Furthermore, these tools also take to job of applying all kinds of optimizations to the generated machine code, since it allows it to be optimal for each target, and also because it improves the performance of dozens of language at once.

But Cranelift has focus on fast compile-time with reasonable runtime performance, and it is also not so mature, so it does not produce heavily optimized code. It is primarily design as a code generator for WebAssembly, so it makes sense to invest more in compile-time speed, where wasm programs are compiled constantly, differently from LLVM for example, that is has more focus on static compilation, where programs are compiled once and run many times.

Basics of Cranelift IR §

Using Cranelift boils down to translation our code to Cranelift’s IR (CLIR), that later get optimized and compiled down to machine code. In the examples below I am showing the CLIR in its textual format, but it is more often manipulated in its in-memory data structure format, as we will see in the next section.

Cranelift’s IR, similar to many others code generators IR, uses static single-assignment form (SSA), which basically means that there is no mutable variables in this representation. Each instruction returns a new value, that is only uses as input of subsequent instructions.

This means that a mutable variable in a high level language would be represented by different values throughout the program. As example:

; x = 3 * (2 + 4)

v0 = iconst.i64 3

v1 = iconst.i64 2

v2 = iconst.i64 4

v3 = iadd v1, v2

v4 = imult v0, v3 // x is in v4

; x = 2*x + 1

v5 = imult v1, v4

v6 = iconst 1

v7 = iadd v5, v6 // now x is in v7

These instructions are contained in basic blocks. A basic block is sequence of instructions, with a single entry at the top, and no branches except at the very end. Branches can only target other blocks. In Cranelift the blocks can receive arguments that allow passing values between blocks.

To implement an if-else expression for example, you would need at least four blocks, the start block, an if block, an else block and the after block:

// x = if v0 != 0 { 1 } else { 2 }

block0(v0: i32):

brnz v0, block1 // branch if not zero

jump block2

block1:

v1 = iconst.i32 1

jump block3(v1)

block2:

v2 = iconst.i32 2

jump block3(v2)

block3(v3):

// x is in v3

A set of basic blocks forms a function, which is the compilation unit of Cranelift. A function has a start block, which inherit the function parameters.

But let’s now see how these are generated in practice.

A Simple Example §

Let’s try compiling the same example that we use in the previous part, the add 1 function. It receives one parameter, adds 1, and return it. In x86 assembly, it was only three instructions:

add rdi, 1 ; the argument is in rdi, I add 1 to it.

mov rax, rdi ; the return value is rax, so I move rdi to rax

ret ; return from the function

We will generate the following correspondent CLIR:

function u0:0(i64) -> i64 system_v {

block0(v0: i64):

v1 = iadd_imm v0, 1

return v1

}

For that we need to make use of the cranelift crate. That crate is an umbrella for two other crates, cranelift-codegen, the core of Cranelift that actually compiles CLIR to machine code, and cranelift-frontend, that is used to write the CLIR.

First we create a Function, that will contain all our CLIR. For that we need

to give it a name (for debugging purposes only), and a signature. Its signature

involves the calling convention (we will use System V, as always) and its

parameters and returns (Cranelift support functions that return multiple

values):

use cranelift::codegen::{

ir::{types::I64, AbiParam, Function, Signature},

isa::CallConv,

};

let mut sig = Signature::new(CallConv::SystemV);

sig.params.push(AbiParam::new(I64));

sig.returns.push(AbiParam::new(I64));

let mut func = Function::with_name_signature(UserFuncName::default(), sig);

To write CLIR to our function we will need a FunctionBuilder. First we

create a FunctionBuilderContext, that is used to recycle resources between

the compilation of multiple functions (something we won’t do). Then we pass both

the Function and the FunctionBuilderContext to FunctionBuilder:

use cranelift::frontend::{FunctionBuilder, FunctionBuilderContext};

let mut func_ctx = FunctionBuilderContext::new();

let mut builder = FunctionBuilder::new(&mut func, &mut func_ctx);

Now we can start the translation! First we create a basic block, that will be the entry of our function. We append the parameters of our function to the block, and switch to it, allowing us to start writing instruction.

We must also remember to seal our block as soon as all branches to it are defined1. Because our function have no branches we can seal it right after creating it.

let block = builder.create_block();

builder.seal_block(block);

builder.append_block_params_for_function_params(block);

builder.switch_to_block(block);

Now we can start writing instructions. We grab the value of the first (and only) parameter of the block, add 1 to it, and return it. And then we can finalize our function.

let arg = builder.block_params(block)[0];

let plus_one = builder.ins().iadd_imm(arg, 1);

builder.ins().return_(&[plus_one]);

builder.finalize();

With this our function is complete! If we want to debug what we have generated, we can print the CLIR:

println!("{}", func.display());

function u0:0(i64) -> i64 system_v {

block0(v0: i64):

v1 = iadd_imm v0, 1

return v1

}

It is exactly what I have showed at the start of the section (I have copy-pasted it there).

Now we only need to compile it. For that we will need to use Context, that

contains everything to compile our function.

First we need to get a TargetISA, that represents the target that we went to

compile to. We get one by passing a Triple from the target_lexicon crate

to isa::lookup. We will use Tiple::host() to get the native ISA of our host

(because we will run on it right after). In out case this is an x86-64 target.

The TargetISA also receives a settings::Flags, that contains some

compilations settings, like the level of optimization.

use cranelift::codegen::{isa, settings};

use target_lexicon::Triple;

let builder = settings::builder();

let flags = settings::Flags::new(builder);

let isa = match isa::lookup(Triple::host()) {

Err(err) => panic!("Error looking up target: {}", err),

Ok(isa_builder) => isa_builder.finish(flags).unwrap(),

};

Now we can compile our function:

let mut ctx = Context::for_function(func);

let code = ctx.compile(&*isa).unwrap();

This returns a CompileCode struct, the machine code can be retrieved with

the code_buffer method.

Now to run it, we can do the same process as we have done in the last part.

But instead of using raw libc calls, lets use memmap2’s safe and

cross-platform abstractions instead:

let mut buffer = memmap2::MmapOptions::new()

.len(code.len())

.map_anon()

.unwrap();

buffer.copy_from_slice(code.code_buffer());

let buffer = buffer.make_exec().unwrap();

let x = unsafe {

let code_fn: unsafe extern "sysv64" fn(usize) -> usize =

std::mem::transmute(buffer.as_ptr());

code_fn(1)

};

println!("out: {}", x);

And if we run the code it prints 2! It works!

But is the generated code any good? Let’s take a look at it. You can use

ctx.set_disasm(true) and code.disasm to get a disassembly generated by

Cranelift, which also contains some extra debug information. But it uses AT&T

syntax, and in this series I am using Intel syntax, so I will save the code to a

file and disassemble it with objdump:

std::fs::write("dump.bin", code.code_buffer()).unwrap();

$ objdump -b binary -D -M intel,x86-64 -m i386:x86-64 dump.bin

dump.bin: file format binary

Disassembly of section .data:

0000000000000000 <.data>:

0: 55 push rbp

1: 48 89 e5 mov rbp,rsp

4: 48 89 f8 mov rax,rdi

7: 48 83 c0 01 add rax,0x1

b: 48 89 ec mov rsp,rbp

e: 5d pop rbp

f: c3 ret

As we can see, if you ignore the pushes and moves use for setting up the stack frame, it generated machine code pretty close to what we have done before.

It is cool that Cranelift also takes care of generating the code for setting up the stack frame, but it is not so necessary for leaf functions like this, even more for such small function.

And in fact, Cranelift is supposed to do that, but this is currently not implemented for x86 (see issue #1148). But it appears to be implemented for AArch64…

So, let’s take a look at AArch64 output! We need to enable the “arm64” features of cranelift-codegen:

# make sure both are in the same version

cranelift = "0.89.2"

cranelift-codegen = { version = "0.89.2", features = ["arm64"] }

And change the target ISA to AArch64:

use target_lexicon::triple;

use std::str::FromStr,

let isa = match isa::lookup(triple!("aarch64")) {

Err(err) => panic!("Error looking up target: {}", err),

Ok(isa_builder) => isa_builder.finish(flags).unwrap(),

};

Of course, we can no longer execute the code, but we can disassemble its output:

$ aarch64-linux-gnu-objdump -b binary -maarch64 -D dump.bin

dump.bin: file format binary

Disassembly of section .data:

0000000000000000 <.data>:

0: 91000400 add x0, x0, #0x1

4: d65f03c0 ret

And look! Only two instructions, no useless stack frame allocation!

Another thing we can look at is what happens when non-optimal code is emitted, for example, if I add 1 two times, one after the other, as we will do in the brainfuck compiler. Could Cranelift be able to optimized it to a single add?

First, let’s enable Cranelift optimizations. For this, we need to use the

settings::builder(), that was used for creating the compiler flags:

let mut builder = settings::builder();

builder.set("opt_level", "speed").unwrap();

let flags = settings::Flags::new(builder);

Now we can emit some non-optimal code:

let arg = builder.block_params(block)[0];

let plus_one = builder.ins().iadd_imm(arg, 1);

let plus_two = builder.ins().iadd_imm(plus_one, 1);

builder.ins().return_(&[plus_two]);

And if we run again and disassemble:

$ objdump -b binary -D -M intel,x86-64 -m i386:x86-64 dump.bin

0000000000000000 <.data>:

0: 55 push rbp

1: 48 89 e5 mov rbp,rsp

4: 48 89 f8 mov rax,rdi

7: 83 c0 02 add eax,0x2

a: 48 89 ec mov rsp,rbp

d: 5d pop rbp

e: c3 ret

Hey, look! A single add eax, 2. It automatically optimized the code for us!

A Cranelift Compiler §

Now we can finally start compiling brainfuck. But first we need to take care of some details.

First, the SSA don’t have mutable values, but brainfuck has a mutable variable, the cell pointer (the mutability of the memory itself will be represented by load/store instructions). So we would need to somehow keep track of what value is the current value of pointer, and keeping passing it between blocks.

But thankfully, codegen-frontend already have a functionality that

automatically manages variables. We only need to create a Variable, and

declared inside our builder. Whenever we need its value, we call

builder.use_var, and when we need to set it we call builder.def_var.

And second, we were using I64 as the type of our values in the last example,

but for the pointer it should have the pointer type of our current target ISA

(as we may change the compilation target later). We can get it by calling

isa.pointer_type().

With all this together, we can start writing our compiler:

struct Program {

code: Vec<u8>,

memory: [u8; 30_000],

}

impl Program {

fn new(source: &[u8]) -> Result<Program, UnbalancedBrackets> {

let mut builder = settings::builder();

builder.set("opt_level", "speed").unwrap();

let flags = settings::Flags::new(builder);

let isa = match isa::lookup(Triple::host()) {

Err(_) => panic!("x86_64 ISA is not avaliable"),

Ok(isa_builder) => isa_builder.finish(flags).unwrap(),

};

// we get the `pointer_type` from `isa`

let pointer_type = isa.pointer_type();

// receive memory address as parameter, and return pointer to io::Error

let mut sig = Signature::new(CallConv::SystemV);

sig.params.push(AbiParam::new(pointer_type));

sig.returns.push(AbiParam::new(pointer_type));

let mut func = Function::with_name_signature(UserFuncName::user(0, 0), sig);

let mut func_ctx = FunctionBuilderContext::new();

let mut builder = FunctionBuilder::new(&mut func, &mut func_ctx);

// create the variable `pointer` (it is a offset from memory address)

let pointer = Variable::new(0);

builder.declare_var(pointer, pointer_type);

let block = builder.create_block();

builder.seal_block(block);

builder.append_block_params_for_function_params(block);

builder.switch_to_block(block);

let memory_address = builder.block_params(block)[0];

// initialize pointer to 0

let zero = builder.ins().iconst(pointer_type, 0);

builder.def_var(pointer, zero);

let mut stack = Vec::new();

for (i, b) in source.iter().enumerate() {

match b {

b'+' => todo!(),

b'-' => todo!(),

b'.' => todo!(),

b',' => todo!(),

b'<' => todo!(),

b'>' => todo!(),

b'[' => todo!(),

b']' => todo!(),

_ => continue,

}

}

if !stack.is_empty() {

return Err(UnbalancedBrackets(']', source.len()));

}

builder.ins().return_(&[zero]);

builder.finalize();

let res = verify_function(&func, &*isa);

if let Err(errors) = res {

panic!("{}", errors);

}

let mut ctx = Context::for_function(func);

let code = match ctx.compile(&*isa) {

Ok(x) => x,

Err(err) => {

eprintln!("error compiling: {:?}", err);

std::process::exit(8);

}

};

let code = code.code_buffer().to_vec();

Ok(Program {

code,

memory: [0; 30_000],

})

}

Now we only need to implement each instruction.

Whenever we need to read the value of the current cell, we will add

memory_address with the value of pointer to get the cell address, and use

load.i8 to read it. To write it back, we use store.i8.

These instructions need a MemFlags, which is used to tell if the memory may

trap, if it is aligned, etc. Let’s use the default for now:

let mem_flags = MemFlags::new();

So for the + and -, we use iadd_imm:

b'+' => {

let pointer_value = builder.use_var(pointer);

let cell_address = builder.ins().iadd(memory_address, pointer_value);

let cell_value = builder.ins().load(I8, mem_flags, cell_address, 0);

let cell_value = builder.ins().iadd_imm(cell_value, 1);

builder.ins().store(mem_flags, cell_value, cell_address, 0);

}

b'-' => {

let pointer_value = builder.use_var(pointer);

let cell_address = builder.ins().iadd(memory_address, pointer_value);

let cell_value = builder.ins().load(I8, mem_flags, cell_address, 0);

let cell_value = builder.ins().iadd_imm(cell_value, -1);

builder.ins().store(mem_flags, cell_value, cell_address, 0);

}

For < and > it is similar, but we also need to wrap around. For that we use

the select instruction, that will be compiled down to a conditional move:

b'<' => {

let pointer_value = builder.use_var(pointer);

let pointer_minus = builder.ins().iadd_imm(pointer_value, -1);

let wrapped = builder.ins().iconst(pointer_type, 30_000 - 1);

let pointer_value = builder.ins().select(pointer_value, pointer_minus, wrapped);

builder.def_var(pointer, pointer_value);

}

b'>' => {

let pointer_value = builder.use_var(pointer);

let pointer_plus = builder.ins().iadd_imm(pointer_value, 1);

let cmp = builder.ins().icmp_imm(IntCC::Equal, pointer_plus, 30_000);

let pointer_value = builder.ins().select(cmp, zero, pointer_plus);

builder.def_var(pointer, pointer_value);

}

Now for [ and ] we need to start creating blocks. So when we reach a [ we

create two blocks, one for the inside of the brackets, and another for after it.

We conditionally jump to one of the blocks based on the current cell value,

using a brz/jump pair of instructions. We switch to the inner block (next

instructions will be written to it), and we finish by pushing the blocks to the

stack.

b'[' => {

let inner_block = builder.create_block();

let after_block = builder.create_block();

let pointer_value = builder.use_var(pointer);

let cell_address = builder.ins().iadd(memory_address, pointer_value);

let cell_value = builder.ins().load(I8, mem_flags, cell_address, 0);

builder.ins().brz(cell_value, after_block, &[]);

builder.ins().jump(inner_block, &[]);

builder.switch_to_block(inner_block);

stack.push((inner_block, after_block));

}

On ], we get the blocks back from the stack, write our conditionally jump

logic, and switch to the after_block. Also, at this point we already have

written all branches to these blocks, so we can seal them.

b']' => {

let (inner_block, after_block) = match stack.pop() {

Some(x) => x,

None => return Err(UnbalancedBrackets(']', i)),

};

let pointer_value = builder.use_var(pointer);

let cell_address = builder.ins().iadd(memory_address, pointer_value);

let cell_value = builder.ins().load(I8, mem_flags, cell_address, 0);

builder.ins().brnz(cell_value, inner_block, &[]);

builder.ins().jump(after_block, &[]);

builder.seal_block(inner_block);

builder.seal_block(after_block);

builder.switch_to_block(after_block);

}

For the . and ,, we will do something similar to our final single-pass

compiler of the last part, and implement them in a Rust function, and call them

from the generated code.

For that we will use the call_indirect instruction. It needs the function

signature and address:

let (write_sig, write_address) = {

let mut write_sig = Signature::new(CallConv::SystemV);

write_sig.params.push(AbiParam::new(I8));

write_sig.returns.push(AbiParam::new(pointer_type));

let write_sig = builder.import_signature(write_sig);

let write_address = write as *const () as i64;

let write_address = builder.ins().iconst(pointer_type, write_address);

(write_sig, write_address)

};

let (read_sig, read_address) = {

let mut read_sig = Signature::new(CallConv::SystemV);

read_sig.params.push(AbiParam::new(pointer_type));

read_sig.returns.push(AbiParam::new(pointer_type));

let read_sig = builder.import_signature(read_sig);

let read_address = read as *const () as i64;

let read_address = builder.ins().iconst(pointer_type, read_address);

(read_sig, read_address)

};

We also need a block to branch to in case of an error:

let exit_block = builder.create_block();

builder.append_block_param(exit_block, pointer_type);

And right after calling builder.finalize():

builder.switch_to_block(exit_block);

builder.seal_block(exit_block);

let result = builder.block_params(exit_block)[0];

builder.ins().return_(&[result]);

So the operations become:

b'.' => {

let pointer_value = builder.use_var(pointer);

let cell_address = builder.ins().iadd(memory_address, pointer_value);

let cell_value = builder.ins().load(I8, mem_flags, cell_address, 0);

let inst = builder

.ins()

.call_indirect(write_sig, write_address, &[cell_value]);

let result = builder.inst_results(inst)[0];

let after_block = builder.create_block();

builder.ins().brnz(result, exit_block, &[result]);

builder.ins().jump(after_block, &[]);

builder.seal_block(after_block);

builder.switch_to_block(after_block);

}

b',' => {

let pointer_value = builder.use_var(pointer);

let cell_address = builder.ins().iadd(memory_address, pointer_value);

let inst = builder

.ins()

.call_indirect(read_sig, read_address, &[cell_address]);

let result = builder.inst_results(inst)[0];

let after_block = builder.create_block();

builder.ins().brnz(result, exit_block, &[result]);

builder.ins().jump(after_block, &[]);

builder.seal_block(after_block);

builder.switch_to_block(after_block);

}

And done! If we run it:

14s, about 4% faster than our single-pass implementation. It is definitely faster, but, well, I was hoping that it would have a bigger improvement by replacing all repeat instructions by a single one.

Let’s take a look at its generated code. Here is the code generated by the

program +++++:

$ objdump -b binary -D -M intel,x86-64 -m i386:x86-64 dump.bin

dump.bin: file format binary

Disassembly of section .data:

0000000000000000 <.data>:

0: 55 push rbp

1: 48 89 e5 mov rbp,rsp

4: 48 0f b6 17 movzx rdx,BYTE PTR [rdi]

8: 83 c2 01 add edx,0x1

b: 88 17 mov BYTE PTR [rdi],dl

d: 83 c2 01 add edx,0x1

10: 88 17 mov BYTE PTR [rdi],dl

12: 83 c2 01 add edx,0x1

15: 88 17 mov BYTE PTR [rdi],dl

17: 83 c2 01 add edx,0x1

1a: 88 17 mov BYTE PTR [rdi],dl

1c: 83 c2 01 add edx,0x1

1f: 88 17 mov BYTE PTR [rdi],dl

21: 48 31 c0 xor rax,rax

24: 48 89 ec mov rsp,rbp

27: 5d pop rbp

28: c3 ret

As we can see, contrary to what I expected, Cranelift was not capable of merging all sums together when they are between a load and a store.

But looking more closely, it was able to remove the redundant loads

(movzx rdx,BYTE PTR [rdi]), but not the stores (mov BYTE PTR [rdi],dl).

Looking around on Cranelift’s GitHub repo, you will find this issue that explains what happened here: the remotion of redundant loads is implemented, but for store it is not.

So, I made a naive implementation of redundant load remotion here

(this probably miscompile some code). Only removing the stores was not enough,

because the optimization pass that merge multiple adds together happened in a

previous pass, so my change also naively rerun all optimizations passes that

looked important.

I got the following emitted code:

$ objdump -b binary -D -M intel,x86-64 -m i386:x86-64 dump.bin

dump.bin: file format binary

Disassembly of section .data:

0000000000000000 <.data>:

0: 55 push rbp

1: 48 89 e5 mov rbp,rsp

4: 48 0f b6 0f movzx rcx,BYTE PTR [rdi]

8: 83 c1 05 add ecx,0x5

b: 88 0f mov BYTE PTR [rdi],cl

d: 48 31 c0 xor rax,rax

10: 48 89 ec mov rsp,rbp

13: 5d pop rbp

14: c3 ret

Much better! But running again shows that does not give much improvement (I forget to benchmark this change, sorry for the lack of precise timings).

Actually, this was to be expected, because an actual improvement only comes from

optimizing the < and > instructions, was we have seen in the first part.

And that one if much more trick to optimize automatically:

# this ones is for the program `>>>+`

$ objdump -b binary -D -M intel,x86-64 -m i386:x86-64 dump.bin

dump.bin: file format binary

Disassembly of section .data:

0000000000000000 <.data>:

0: 55 push rbp

1: 48 89 e5 mov rbp,rsp

4: b8 01 00 00 00 mov eax,0x1

9: 48 83 c0 00 add rax,0x0

d: 48 31 c9 xor rcx,rcx

10: 48 81 f9 30 75 00 00 cmp rcx,0x7530

17: 48 0f 43 05 49 00 00 cmovae rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x49] # 0x68

1e: 00

1f: 48 89 c1 mov rcx,rax

22: 48 83 c1 01 add rcx,0x1

26: 48 81 f8 30 75 00 00 cmp rax,0x7530

2d: 48 0f 43 0d 33 00 00 cmovae rcx,QWORD PTR [rip+0x33] # 0x68

34: 00

35: 48 89 ca mov rdx,rcx

38: 48 83 c2 01 add rdx,0x1

3c: 48 81 f9 30 75 00 00 cmp rcx,0x7530

43: 48 0f 43 15 1d 00 00 cmovae rdx,QWORD PTR [rip+0x1d] # 0x68

4a: 00

4b: 4c 0f b6 44 17 00 movzx r8,BYTE PTR [rdi+rdx*1+0x0]

51: 41 83 c0 01 add r8d,0x1

55: 44 88 44 17 00 mov BYTE PTR [rdi+rdx*1+0x0],r8b

5a: 48 31 c0 xor rax,rax

5d: 48 89 ec mov rsp,rbp

60: 5d pop rbp

61: c3 ret

Here it is less obvious how a program could detect that these three cmovae can

be replaced by a single one.

But to be fair, Cranelift is design to have faster compilation times, and may not be prepared to optimized such a bad emitted IR.

So let’s optimize these repeated operations during translation. I will not implement the three remaining optimizations yet, because I think they will not be necessary.

First let’s make the source iterator be peekable, and filter out non-instruction symbols:

let mut ops = source

.iter()

.enumerate()

.filter(|x| b"+-><.,[]".contains(x.1))

.peekable();

while let Some((i, &b)) = ops.next() {

// ...

}

And on +, -, < and >, we first count how many of these instructions we

have, and then emit the optimized IR:

b'+' | b'-' => {

let mut n = if b == b'+' { 1 } else { -1 };

while ops.peek().map_or(false, |y| b"+-".contains(y.1)) {

let b = *ops.next().unwrap().1;

n += if b == b'+' { 1 } else { -1 };

}

let pointer_value = builder.use_var(pointer);

let cell_address = builder.ins().iadd(memory_address, pointer_value);

let cell_value = builder.ins().load(I8, mem_flags, cell_address, 0);

let cell_value = builder.ins().iadd_imm(cell_value, n);

builder.ins().store(mem_flags, cell_value, cell_address, 0);

}

b'<' | b'>' => {

let mut n = if b == b'>' { 1 } else { -1 };

while ops.peek().map_or(false, |y| b"<>".contains(y.1)) {

let b = *ops.next().unwrap().1;

n += if b == b'>' { 1 } else { -1 };

}

let pointer_value = builder.use_var(pointer);

let pointer_plus = builder.ins().iadd_imm(pointer_value, n);

let pointer_value = if n > 0 {

let wrapped = builder.ins().iadd_imm(pointer_value, n - 30_000);

let cmp =

builder

.ins()

.icmp_imm(IntCC::SignedLessThan, pointer_plus, 30_000);

builder.ins().select(cmp, pointer_plus, wrapped)

} else {

let wrapped = builder.ins().iadd_imm(pointer_value, n + 30_000);

let cmp = builder

.ins()

.icmp_imm(IntCC::SignedLessThan, pointer_plus, 0);

builder.ins().select(cmp, wrapped, pointer_plus)

};

builder.def_var(pointer, pointer_value);

}

Running it again:

Much faster! But it is still slower than our optimized compiler.

So I gave up on the idea that, currently, Cranelift could apply enough optimizations to replace our optimizations.

So, here is the implementation for the optimized instructions. The

MoveUntil instructions was not included, because I noticed that it does not

help in generating better optimized code:

Instruction::Clear => {

let pointer_value = builder.use_var(pointer);

let cell_address = builder.ins().iadd(memory_address, pointer_value);

builder.ins().store(mem_flags, zero_byte, cell_address, 0);

}

Instruction::AddTo(n) => {

let n = n as i64;

let pointer_value = builder.use_var(pointer);

let to_add = builder.ins().iadd_imm(pointer_value, n);

let to_add = if n > 0 {

let wrapped = builder.ins().iadd_imm(pointer_value, n - 30_000);

let cmp = builder

.ins()

.icmp_imm(IntCC::SignedLessThan, to_add, 30_000);

builder.ins().select(cmp, to_add, wrapped)

} else {

let wrapped = builder.ins().iadd_imm(pointer_value, n + 30_000);

let cmp = builder.ins().icmp_imm(IntCC::SignedLessThan, to_add, 0);

builder.ins().select(cmp, wrapped, to_add)

};

let from_address = builder.ins().iadd(memory_address, pointer_value);

let to_address = builder.ins().iadd(memory_address, to_add);

let from_value = builder.ins().load(I8, mem_flags, from_address, 0);

let to_value = builder.ins().load(I8, mem_flags, to_address, 0);

let sum = builder.ins().iadd(to_value, from_value);

builder.ins().store(mem_flags, zero_byte, from_address, 0);

builder.ins().store(mem_flags, sum, to_address, 0);

}

And the results:

Now it is faster that our previous implementation! At least, we got something from using Cranelift.

It is also important to notice that the times that I measure here takes in account the running time of the entire program, including the compilation time. Mandelbrot takes at least 100ms to compile, and factor 30 ms, which are already significant times.

But of course, optimizations is only one the strengths of using a machine code generator. Because now our compiler can target 3 different architectures! We have x86-64, AArch64, s390x and however backend they add in the future!

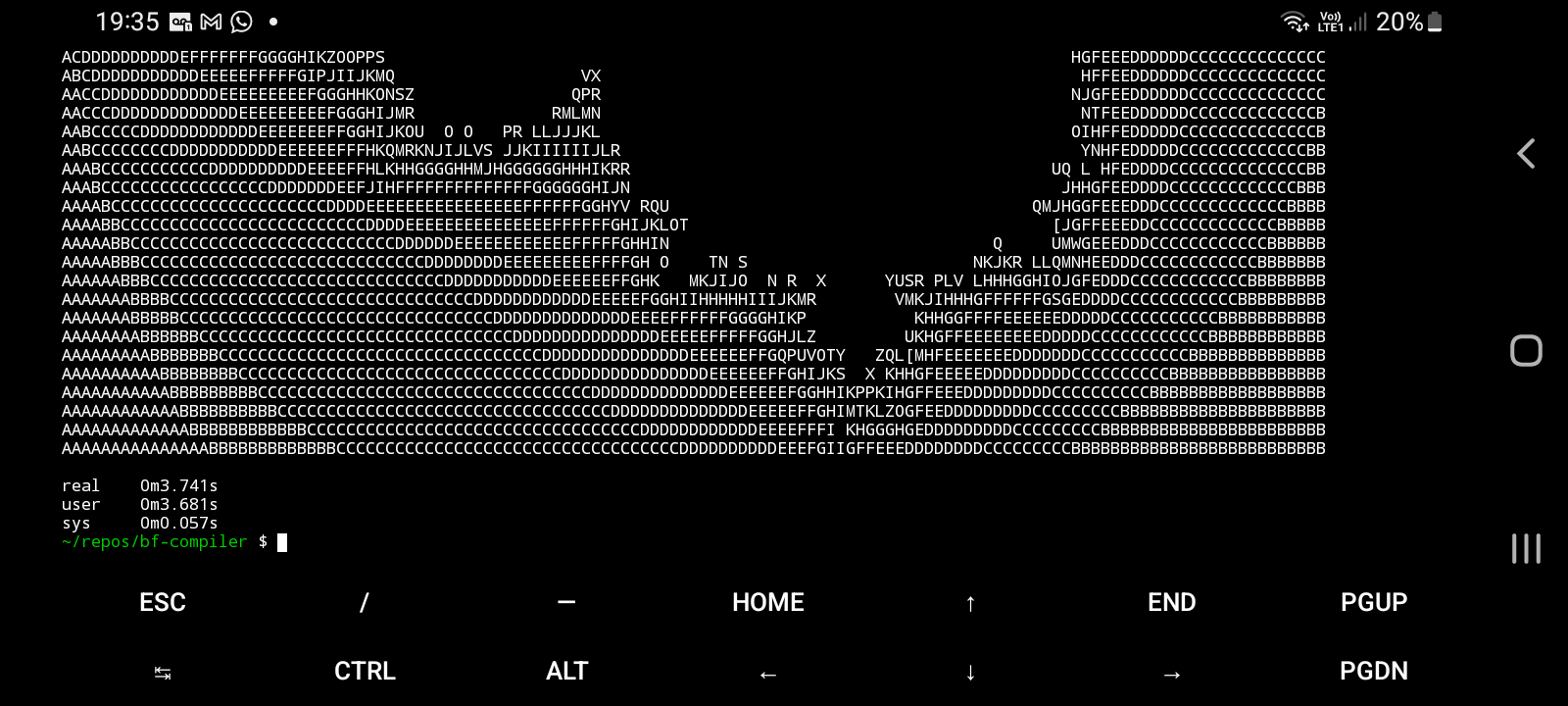

After changing ABI’s of the functions to the host default (we don’t need to stick to a single calling convention anymore), I was finally able to run our compiler on my smartphone (an AArch64), using Termux:

Cool!

Conclusion §

At the start of this post I have no idea of how good Cranelift optimizations were. Ideally it would be able to automatically figure out all the optimizations that we came up in the first part. At the other end, it would emit suboptimal machine code, and be slower than our handcrafted implementation.

In the end, we verified that the second scenario didn’t occur, the generated code was actually faster than our implementation.

However, it was far from the first one: even the basic optimization of combining

multiple + didn’t happen by default (at least I was able to implement it in

Cranelift fairly easy, despite being hackish).

Yet, it accomplished our main goal of using a machine code generator: be able to target multiple architectures with only a fraction of the knowledge and work required.

Note that this post is not showing that Cranelift optimizations are bad, but how bad brainfuck is. Brainfuck only has a single persistent variable and almost every instruction need to read and write to memory.

This means that many of Cranelift optimizations passes are completely underexplored, because they are designed for languages that have multiples values being passed around (more than there are CPU registers), as is the norm for most programming languages.

Future work §

Since the beginning of this series we are optimizing our brainfuck implementation more and more. In fact, we could continue creating more and more optimizations to our program, making the execution of out brainfuck programs be faster and faster.

But as we go applying these optimizations, the time necessary to parse and compile the code starts to become greater and greater. To such a point, that applying more optimizations will not actually decrease the time we need to wait to get a brainfuck program to run.

At that point, having such a degree of optimizations is not viable when creating a JIT compiler.

To solve this, we can instead make an AOT compiler2. Instead of waiting for the compilation every time we need to run a program, we can instead compile it just one, ahead-of-time (AOT), and serialize it to disk. Now, the user can load and run the program as many times as they want, without needing to wait for the compilation.

And this is exactly what we will do in the next part. We will see how we can get our generated machine code and serialize it to an executable file, like a ELF file.

All the code developed during these series can be found here (may not be exactly equal to one showed here).

-

Sealing them as soon as possible allows the resolving of

Variables to be faster. I present and useVariables when we start making our brainfuck compiler. ↩ -

I used the term “AOT” here to have a contrast with “JIT”, but it is a term more used in context where the language is expected to be JIT compiled. Normally, the term “compiled language” already implies that the language is compiled ahead of time. AOT is also used in scenarios where the compilation is not emitting machine code directly, so “static compiled” or “native compiled” may be better suitable to “compiled languages” than “AOT compiled”. ↩